Salutations from Santorini, dear reader. That’s what I’d be saying right now — if I had a dollar for every single time I was asked… ”How low should you squat?’

So, How Low Should You Squat?

Well, like most things often OVERcomplicated, it can be a little complex.

Short answer… Generally go as deep as you can if:

- It’s pain-free

- You have enough mobility to get there

- You can coordinate/control it and technique looks good

- You’re comfortable doing it and want to do it

- The aim is powerlifting, hypertrophy, aesthetics or general strength

- You don’t look like a pooping dog while you’re doing it.

I apologise for that last one, but you know what I mean.

My general rule of thumb is this:

Go as far as you can, but no further.

Which means don’t try to force it if it’s not there. Some of us are not built for it. Chances are if you’ve always been able to deep squat, butt to calf muscles, you’ve chosen your parents well. To keep it, you need only groove it with constant repetition.

For others, thighs parallel to the ground is the last stop. Beyond which might result in a trip to physical therapy.

Even as a strength coach, I’d like us to rethink the value we place on certain exercises.

We often discuss external variables. Movement patterns, buttwink, and strength standards. Apply a made-up rubric of arbitrary hip joint and knee flexion angles. As though the hips and knees of all humans can move, absorb and adapt to stressors similarly.

I’d like us to consider more the internal metrics of individual needs, wants, and costs. As well as differentiate between transfer and value.

Rethinking Squat Depth

The squat depth that you hit depends on the squat depth that YOU can hit. Not on the hip crease angle that someone else says you should reach.

We all bring to the squat rack a completely different constellation of biological stuff. Different wiring, springs and hinges to tackle this mundane task. A made-up exercise that really, only a gifted few have the goods to achieve according to holy-squat lore.

What we have at best is a general template for what ‘good squat form’ looks like. A range to work within. Good form is if you need to be there, and can be.

The deep squat as a movement is an expression of mobility. Flexibility and control according to narrow constraints. Let’s not forget, the hips alone are cable of exploring many other degrees of motion.

Squatting as a barbell exercise is just a tool of strength training.

You can apply it several different ways. Emphasising different joint angles, velocities, and muscle contraction types. Depending on the outcome you want to provoke.

However, the squat exercise comes with a rather narrow set of mean criteria. Has a laundry list of structural and behavioural requisites. And dare I say, far less transfer in the larger scheme of movement possibilities than we like to think.

All of this rambling is to say:

Excursion of range in a pre-determined movement that someone else invented is not a proxy for health.

For many, no matter how much stretching or YouTubing we do to improve squat depth…

We’ll never have the ankles, shoulder and hip socket anatomy for squatting deep. Never mind while supporting a loaded bar on our back.

But, Why Should We Use a Full Range of Motion?

Well, a couple of reasons. Some of the benefits of squatting below parallel to the floor include:

1. More complete stimulus and development across the full length of the muscle

2. Greater hypertrophy through increased mechanical tension

3. Improves and maintains flexibility and mobility

4. Get strong and stable at long lengths (where we are weakest)

5. Less injury risk as the load is dispersed across more joints/tissue. This does not mean you can prevent injuries.

6. It standardises your squat technique so you can better gauge your progress

Again, that’s if your joints can move, absorb and adapt to the training that you wanna do. And the results that you want to deliver.

Related: Arnold Press Muscles Worked and Comparison With the Dumbbell Shoulder Press

Full Range of Motion Squats

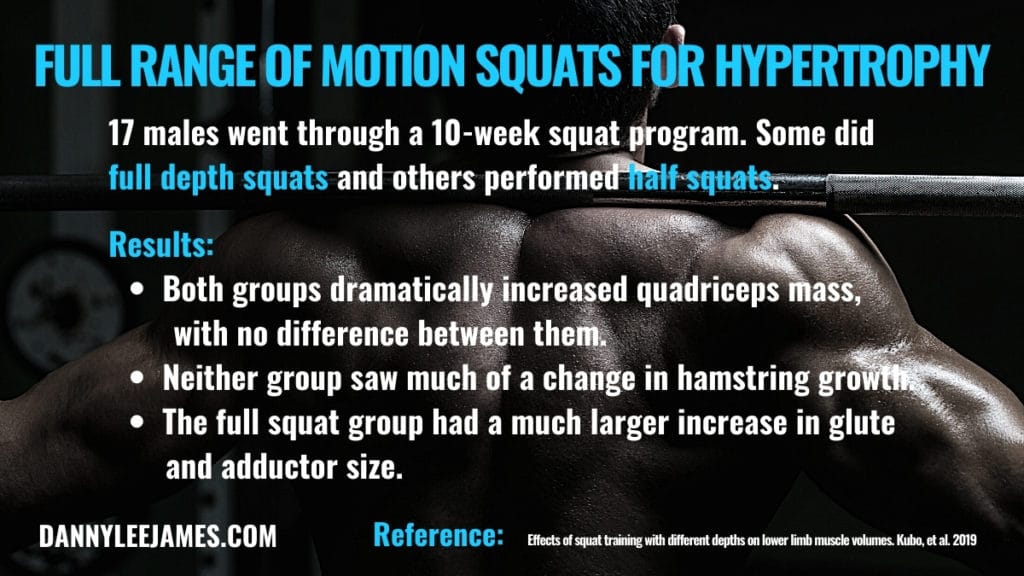

In a 2019 study, researchers put 17 males through a 10-week squat program. Some participants did full depth squats and others performed half squats (1).

The results:

- Both groups dramatically increased quadriceps mass, with no difference between them.

- Neither group saw much of a change in hamstring growth

- The full squat group had a much larger increase in glute and adductor size.

If those are your goals, then squat depth should be as low as you can get to, safely.

Now, there’s also plenty of argument for the other side of the coin.

Partial Range Squats

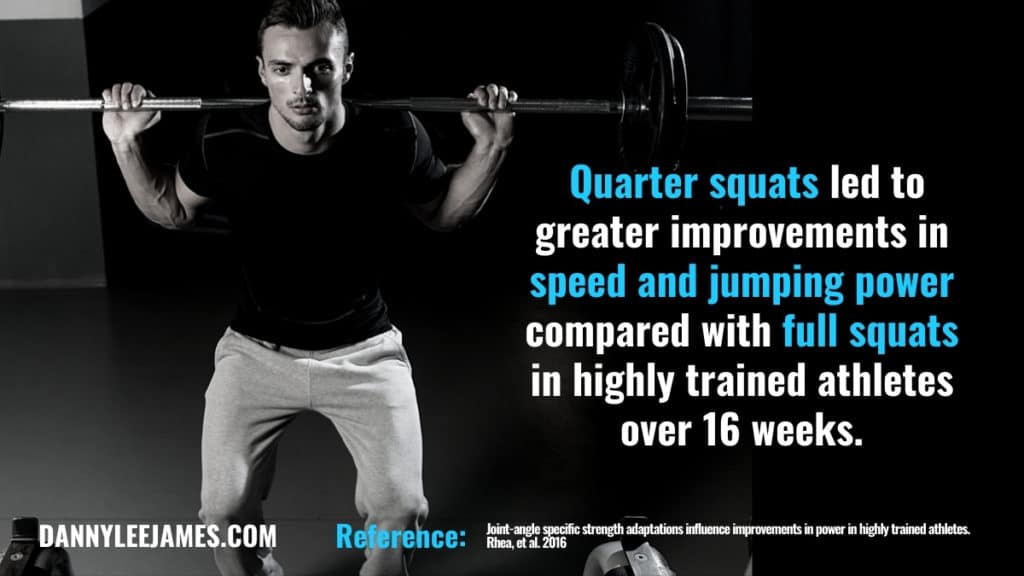

Partial-range squats can be helpful if you want to overload a particular point in the range. Because we get strong at and around the joint angles we train at. Runners and sprinters for example, can benefit from partials because those are the angles they perform from. Very rarely do they hit those bottom situations in flight.

Rhea et al explored this in 2016 with highly trained athletes over 16 weeks. They found that quarter squats led to greater improvements in speed and jumping power compared with full squats (2).

It all depends on what you’re aiming for. And the biology you’re bringing to the squat rack.

Final Thoughts On Squat Depth

Unfortunately, there can be no one-size-fits-all squat depth formula. All we can really say is the best squat depth for you, is the one that minimises cost.

So, to close us out dear reader, remember:

Wherever the bottom of the squat is for you is up to you and your needs. Go as far as you can, but no further. In general. Or, take it to 90 degrees (or less) of hip flexion if specificity demands it.

There are benefits waiting for us at both ends (3).

At least you know the price.

References

- Effects of squat training with different depths on lower limb muscle volumes. Kubo, et al. 2019

- Joint-angle specific strength adaptations influence improvements in power in highly trained athletes. Rhea, et al. 2016

- Effects of changing from full range of motion to partial range of motion on squat kinetics. Drinkwater, et al. 2012

[…] Get strong in the stretch […]

[…] How Low Should You Squat? […]

[…] And that is, that squats are hard. […]

[…] aim was to determine if free weight squats really were better at improving strength, speed, jumping power and […]

[…] have space to move with ease and abandon, through an array of movement patterns and plains. Not to mention, the flexibility of being able to work through a variety of velocities depending on […]

[…] Previous research has suggested that passive interset stretching might positively influence neuromuscular, metabolic, and hormonal responses to training, largely resulting from the increased total time under mechanical tension. […]

[…] heavy squat uses more muscle groups, is much harder and will burn more total energy. And as well talk about in […]

[…] if the goal is weight loss or burning fat around the abdomen, would you squat or […]

[…] always though, an audit for suitability is best to determine if it’s a worthwhile addition to a program. For the obvious reasons of […]

[…] This is because of the heavy eccentric loading as we move into end ranges. As we’ll discuss, high-tension at long muscle lengths is usually more hypertrophic […]

[…] each rep through the fullest range of motion possible with knees […]

[…] You want to train your shoulders through a fuller range of motion. […]

[…] squats, for example, will cause a greater relative contribution from the quadriceps. You'll also see this play out in a military press where the upper arms move predominately in the […]